Previous: And then just coast (1)

Next: The Art Writings of Darby Bannard (18)

New in the WDBA: George Bethea

Post #1430 • December 11, 2009, 8:23 AM • 248 Comments

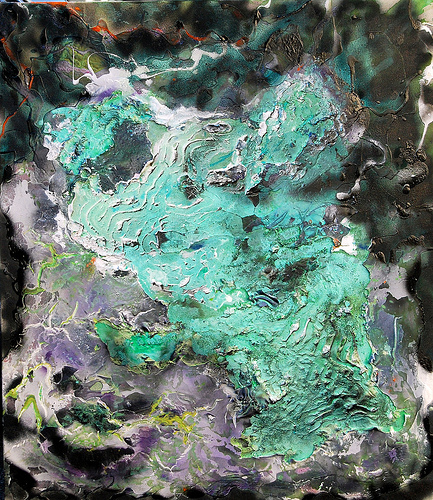

George Bethea: Moss Man, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 40 inches

George Bethea continues to be one of the very best artists of his generation, one of a small group of ambitious, original painters in Miami working at a very high level with little recognition. That he is not celebrated for his accomplishments says more about the Miami art world than it does about his work. It certainly accords with the modern tradition of obliging the best to work in relative obscurity. Perhaps it should not be surprising in a time when art can be anything and therefore usually amounts to nothing.

Read the whole essay.

2.

December 11, 2009, 10:34 AM

This one is great!

3.

December 11, 2009, 10:50 AM

I have some issues with this essay, but I am not about to get into them here. I do, however, offer this quote from an interview I read in a publication called Works & Conversations.

EMC: Being ethical away from the world is easier than when we are involved ourselves. I think some people see the path of abstraction as pure, uncompromised, but it’s a purity of avoidance instead of distillation of what’s essential. And that goes for art too; artists who insist on removing their work from human struggles take an easier path, an easier path that seems particularly wasteful when we know that many live themselves in turmoil and confusion.

This is more of a personal issue I have with Abstract Expressionism, than with this work.

4.

December 11, 2009, 11:52 AM

DCP, this sounds like the old "abstract art lacks humanity" argument people used to hassle about 50 years ago.

Is it?

If so, answer this: does instrumental music also "lack humanity"?

5.

December 11, 2009, 12:09 PM

DCP: Of course EMC is right to say "being ethical away from the world is easier than when when we are involved". However, the suggestion that therefore art, to be ethical, must be "involved" is beside the point of art, though quite in keeping with a lot of the explanations that are commonly attached to art. Involving art in ethics is the easier path, not vice versa as EMC asserts. A couple of years back, the explanation of the poop machine at the New Museumas a work that explored "bio-ethics" helped put it over. Large crowds gathered each day at the appointed time for it to release its waste, and every last specimen sold for $1,000 each. The association with the noble cause of bio-ethics made it much much easier for everyone to regard the piece as important as well as fun. It probably was fun, too, though hardly important.

Art, both good and bad, has a poor record of solving human problems. The poop machine didn't improve the bio-ethical situation, though no one seemed bothered by that fact. Propaganda art in the former Soviet Union did (apparently) succeed in helping their citizens temper any public statements against their government by reminding citizens that the government was totalitarian and might get them for deviation from the program. Though close to what the art was supposed to do, compliance out of fear fell a little short of its ambition to make happy citizens out of the Soviet people, who ultimately revolted against that government. And of course Goya - how many wars did he prevent?

But for artists in personal "turmoil and confusion" the discipline of art therapy might have something to offer. As I understand such therapy, the aesthetic result isn't important to the therapeutic effect, nor is the therapeutic effect necessarily going to extend itself to anyone except the patient under treatment. In short, art as therapy is something quite a bit different than what Bethea or most other artists who show in public seek to create.

Tim Lefens, who started Art Realization Technologies, has found the greatest positive effect making art has on his disabled clients takes place when he disallows their problems as an excuse for making anything less than the best they can make. By making art that stands on its own, without reference much less indulgence in their own "turmoil and confusion" (of which they have plenty), they wind up feeling better about themselves. I would call this the dignity that comes with honest work, but then I'm old fashioned that way.

As far as the AbEx nutty artists go, one of the most popular contemporaneous interpretations of their art was proffered by Harold Rosenberg. He said for them their art and their life were the same thing, with literally no distinction between the two. So, if you believe Rosenberg, they avoided what EMC calls the "easier path", not the opposite.

But you are right that many here understand art to be autonomous, that this autonomy is indeed part of its gift to those of us who are alive, by providing a time-out from life's issues in which we can experience the pleasure art alone can provide. But it is exactly this - a time out - and nothing more. Life, if one is forced to choose between life and art, is more important than art. If buying art supplies means you can't afford to buy food for your children, you don't buy art supplies.

Now, there is some appeal in the statement that removing work from human struggles is "wasteful" even if we know art can't resolve those struggles. I mean why devote time, energy, and resources to art when people are homeless and starving in our streets? But then, the same rhetoric applies to why watch the Super Bowl? Why play golf? Why do anything until that problem is solved? And when that problem is solved there are plenty others that should not be allowed to exist.

Well, I'm not God so I don't have an answer to such ultimate questions. The world as it exists is full of crap that seems odious and problematic, but it has some wonderful stuff too. Art can only do what it can do, and must exist, if it wants to exist, in this context.

6.

December 11, 2009, 12:12 PM

Beautiful Paintings ! Excellent essay! Can't ask for more !

7.

December 11, 2009, 12:19 PM

the painting is interesting to look at.some on his flickr site are actually beautiful. i would like to see more.

8.

December 11, 2009, 12:23 PM

@opie: No. I did not mention anything concerning lack of humanity in Abstract Expressionism.

@John: I don't think art is supposed to solve human problems, but can be a tool for clarity. Which, I think, is where EMC is going with this, and where Ab Ex falls short.

9.

December 11, 2009, 12:25 PM

George Bethea appears to be joining Susan Roth in making a visual case for "tough painting". There is some "difficulty" in seeing this picture at first, but when I work my way through that, it is smooth sailing, just like when a plane breaks across the sound barrier and gets to the smooth air on the other side. His "rawness" is only apparent, not the effect of defects. But it does take some getting used to, like much work that elects to use a direct path to its final result.

10.

December 11, 2009, 12:34 PM

Lucas, what about this painting makes it great?

11.

December 11, 2009, 12:41 PM

DCP: Are you unaware that clarification is one of the most important steps in solving human problems?

But I like "can be a tool for clarity". You seem to be backing off from "must be a tool for clarity". And yes, AbEx did not clarify anything about life, Harold Rosenberg to the contrary.

However, unless you really mean "must be a tool", it does not follow that AbEx "falls short" because that phrase is pejorative and not warranted if there is no mandate for art to do such things.

For a thoughtful, thorough statement about art and moral values, try this.

12.

December 11, 2009, 12:45 PM

It looks like a dragon. Moss Dragon.

Bethea's work continues to remind that painting isn't dead and pop/shock junk is nowhere near as meritous of a show.

13.

December 11, 2009, 12:56 PM

John, I am aware that clarity is a step, one of many, towards solving human problems.

Who said that art "must be a tool"?

Thanks for the article.

14.

December 11, 2009, 1:07 PM

No one here, so far, DCP, has said that. But it is implied when you use a phrase like "falls short" with respect to AbEx's "failure" to clarify.

A different example. Let's say I said: "The annual football game between Oklahoma and Oklahoma State falls short of clarifying the issues involved in giving a 'peace prize' to a commander-in-chief who is conducting two wars in foreign countries, both far distant from his own". That wouldn't make much sense, would it? Football games are not mandated to provide such clarification. The fact Okies call this game "bedlam" might be a lever for an art critic to associate it with such clarification, but most people of common sense will say it's just a game, and all it clarifies is which team scored the most points on the day the contest was held. They might even feel the art critic was a little nutty.

15.

December 11, 2009, 1:21 PM

No, the football statement does not make much sense. I don't pretend to hold football or the Nobel Peace Prize on the same plane as art. In addition, art is not mandated to do anything. Paintings like these tend to make me think of watching TV, though.

I guess I hold my idea of art on a higher level than entertainment.

16.

December 11, 2009, 1:23 PM

This reproduction is very handsome, though as always I can't evaluate any work properly in reproduction. I wish George had sent me an announcement for the show,though. I would certainly have mentioned it in my column (as I have with previous shows of his).

As followers of that column know (or those who have read my book) I don't believe that abstract art is "removed" from the world at all. I say it's connected (though in a different kind of way).

That said, there is also no justification for the claim that any kind of art (abstract or representational) must focus on the troubles of the world, as opposed to its beauties. Any more than that every play should be a tragedy, and that comedy is an inferior art form.

17.

December 11, 2009, 1:44 PM

"Art is a human activity having for its purpose the transmission to others of the highest and best feelings to which men have risen." -- Lev Tolstoy

Where did art assume any other function than conveying beauty and/or emotion? Why all this talk of "clarity" or solving the world's problems through art?

Abx conveys beauty and emotion just as well as any style.

18.

December 11, 2009, 1:49 PM

john (with a little j), if you have to ask, you are not going to be able to 'see it' even if it were explicable. One of the regulars on artblog came up with a new category of art the other day called 'explainable art' (I think it was big John who coined the phrase). George's paintings are a country mile from whatever that encompasses. I guess you are just going to have to take my word for it.

20.

December 11, 2009, 2:25 PM

OK, DCP, let me ask you in your own words.

Is instrumental music "a purity of avoidance" and "an easy path", and are these musicians "removing their work from human struggles"?

This is a discussion blog. When you make an assertion you are expected to be able to back it up, not weasel out with semantics.

21.

December 11, 2009, 2:32 PM

And when we get through with that, let's talk about scientists.

That Einstein was certainly some kind of avoider of human struggles with that E=MC2 stuff.

22.

December 11, 2009, 2:42 PM

Little john, you might try reading the essay.

That may help, or it may not.

23.

December 11, 2009, 2:45 PM

Opie, those were not my words. However, to attempt to answer your question, I would say that music and art, for me, are perceived differently and no, instrumental music does not do those things.

Second, I know what this blog is, as I have been following it for some time now, but thank you for your insight.

24.

December 11, 2009, 2:58 PM

"Instrumental music does not do those things."

OK. But given that instrumental music does not represent or involve human struggle (or whatever it is that whomever you are quoting and which gives you trouble etc etc) is it some other factor in abstract art apart from its lack of subject matter that is the problem? If so, can you tell us what that is?

Please be specific.

25.

December 11, 2009, 3:14 PM

The problem I have with abstract art is, partly, its claim of purity and a feeling I get when looking at it that reminds me of people who mainly talk to hear themselves speak.

To comment on the last sentence that Franklin posted from the WDBA article I feel like abstract art cannot claim to be any higher than the "art that can be anything and amounts to nothing," when it is about nothing other than fleeting emotions. (Emotions are connected to thoughts, which can lead to clarity, depending on the thought of coarse.)

26.

December 11, 2009, 3:25 PM

The "whole essay" doesn't do Bethea justice, it spends too many words on what Bethea is not. Marketing 101: Promote the product, not the competition.

DCP in #3 is quoting EMC and clearly EMC doesn't understand some things about art that are essential. The point in incorrect and should be ignored.

The flaw in many discussions of abstract paintings is that they don't address how the works are perceived by the viewer. I am cautious about discussing Bethea's paintings because I haven't ever seen one but I'll throw caution to the wind for a moment.

What holds Bethea's paintings together is their consistent pictorial space, a space which references our knowledge of the photographic.

His spacial structure serves to locate the viewer in a specific way, in Moss Man we are arial, looking down on a topology. Again, hampered by only having a reproduction, topology means that I am viewing a surface, or at least only a shallow depth relative to the surface. The gestural movement is imbedded in this surface removing it somewhat from an the gestural association with the artists hand.

In the Eggo (see comment #1) the viewers location is less specific but the sensation is one of looking into or down into a liquid space with the various pictorial elements floating at various levels within this space. This is considerably different than what occurs in Moss Man, the scale differences between the floating elements forces the pictorial space to be much deeper, relatively bottomless. Moreover, by allowing the various squiggles to float, their gestural qualities remain intact allowing the viewer to empathetically connect with the artist in a kinesthetic fashion. It's more "humanist."

27.

December 11, 2009, 3:38 PM

I read the Celaya interview. In a way, he's repeating the sentiment of Guston, whose feelings about what was going on in the world caused him to lose interest in abstraction, and goaded him to take up politically and socially charged imagery, not that doing so made the paintings effective as political action or political commentary. I sympathize with this even though it doesn't pan out rationally. It speaks of a kind of emotional morality that motivates an ethical life - the mistake would be to base too much upon it. Like policy, for instance.

Abstract art doesn't make any claim to purity, only a claim to abstraction. People who like to hear themselves talk tend to stay away from it because it doesn't lend itself to exegesis. I don't want to presume, but it frequently happens that people who think that abstraction is some kind of cult of purity typically have misunderstood certain writings by Clement Greenberg, or have heard critiques of a distortion of something he wrote. No 20th Century thinker is known so wholly in the form of caricature, so this isn't terribly unusual, though it is terribly unfortunate.

At any rate, abstraction isn't any more about fleeting emotions than it is about politics. That it can convey emotion is a side-effect that makes it identifiable as art, but this is not the point of abstraction. Abstraction is simply a limited way of working. Fruitful action in art requires limits of some kind, which is why the state in which everything can be art ends up amounting to so little. That doesn't mean that abstraction is a preferable limitation in all cases. Neither does it mean that any other limits would be equally fruitful. There is something particularly interesting and wonderful about the problem that causes talented people like George to produce great work.

28.

December 11, 2009, 3:56 PM

Just an aside: I note that Mr. Bannard briefly mounts his acrylic medium hobby horse in the essay, and I wanted to add that I've seen a number of artists working with acrylic medium and adjusting the pigments and so forth. Two that immediately come to mind are Steven Alexander and David Mann.

I'm not sure that either of them are working at the high level cited of Bethea here. I can't really judge since I've never seen Bethea's work in person. Neither Alexander nor Mann struck me as GREAT or anything, but within their ranges they're at least good.

The point is, though, that the "relatively new" acrylic mediums are being exploited more and more, which should make Mr. Bannard happy.

29.

December 11, 2009, 3:57 PM

OK Franklin thanks for saving me the trouble. I thought DCP had some sort of worked-out rationale but it seems to be simple petulance stemming from fantasized claims of snootiness on the behalf of abstract artist. He must have had a bad experience. I should have known better.

30.

December 11, 2009, 4:04 PM

Franklin than you very much for the post. As always, I appreciate your support.

Good comments!

The show went pretty well.The worked looked good but not good enough. I knew a head of time it would be up for only 2 weeks. Not ideal, but I wanted to get these seen and didn't want to wait.

31.

December 11, 2009, 4:05 PM

Chris there is a difference between "working with" and "exploiting". "Exploiting" means really taking advantage of the material. finding out what arylic can do that is differerent from oils, different from just working colored paste around a flat surface with a brush.

Few people have done this, and I have not seen it effectively taught.

32.

December 11, 2009, 4:07 PM

Opie, for the record, I don't appreciate the jab. I was simply trying to state my opinion, which is obviously very different from yours. I'm sorry you feel lead to degrade my opinions.

33.

December 11, 2009, 4:10 PM

Piri, I did send you a brochure and invitation. I'll get another one out this weekend. Thanks for letting me know.

34.

December 11, 2009, 4:22 PM

DCP, it's one of the sad facts of online forums that no one ever thinks that they threw the first jab. Thank you for your participation.

35.

December 11, 2009, 5:55 PM

Reactions to photos of Geo. Bethea's paintings:

The paintings are something like Soutine or perhaps Tamayo (or others) just before they start putting the details in.

Bethea proceeds to the point just before his composition gels into a tableau or at least identifiable stuff. His paintings give a collection of flavors that combine to become a dish just before they would've spelled something out literally. They're not especially challenging and they don't really take me anywhere I haven't been, but the trip is nonetheless pleasant.

36.

December 11, 2009, 6:16 PM

Tim, what do you mean by challenging? Can you give me an example?

37.

December 11, 2009, 6:24 PM

Although the Bethea show is down, the Darby Bannard retrospective is still up. For those in or visiting the Miami area who'd be interested in seeing it, all necessary info can be found here.

A couple of images from the Bannard show:

Courier (7/09)

Gideon (5/08)

38.

December 11, 2009, 6:25 PM

Sorry, DCP. I guess I was just disappointed because I thought a good debate might be shaping up, and I love a good debate.

39.

December 11, 2009, 6:47 PM

moss man does look good.

and from page one on his flickr.com site i especially like ry, rr, both ananke pics and #4. #5 on page one is nice as well and somewhat in the style of moss man.

#4 seems like it just happened in a mysterious way and is super with fine color. and based on george's older pics i thought it would have been very built up and heavy, but for the most part the application is thin and delicate (excluding the cream/white based form).

40.

December 11, 2009, 6:49 PM

george why do you say it did not look good enough?

41.

December 11, 2009, 7:03 PM

OP sez:

Finding out what arylic can do that is differerent from oils, different from just working colored paste around a flat surface with a brush.

Maybe it's not clear from the JPEGs, but I thought of those artists in particular because they're both doing something with acrylics that is different from oils. In person it's clear the surface isn't oil paint -- in parts it looks almost encaustic. What both of them do is play with the opacity and body of the acrylic medium, adding pigments in different proportions.

I suppose you could maybe do that in oils, if you mixed your own from scratch, but who does that?

Alexander's work has a low-relief sculptural quality, also. And he confessed to me using acrylics saves him on shipping: One of his galleries is in Texas, so he takes the canvas off the stretchers, rolls it and mails it, and the gallery restretches it at the other end. You could do that with oils, but not too many times, I don't think.

42.

December 11, 2009, 7:05 PM

Franklin sez:

It's one of the sad facts of online forums that no one ever thinks that they threw the first jab.

I do, sometimes.

43.

December 11, 2009, 7:14 PM

1 Compressed space would make any sensible artist say what was said. George's paintings need space. Enough said.

44.

December 11, 2009, 7:18 PM

You are right, Chris. They both seem to be using acrylic mediums to get characteristic acrylic effects, especially Mann, although Alecander is by far the better painter.

Unfortunately it is very hard to tell from the photos, which I think are rather poor in either case.

I have seen Alexanders paintings before and I think he is damn good. One of the few who manages color nicely.

45.

December 11, 2009, 7:21 PM

DCP, for the record, I enjoyed my exchange with you. It went far enough to reveal what are respective positions are, and I thought your accommodation of our differences was quite civilized, as I hope mine was too. Keep on commenting, please.

46.

December 11, 2009, 8:26 PM

1- just an attitude that the work can always be better. It's not uncommon among artists.The urgency to get back to work is there.

47.

December 11, 2009, 8:39 PM

George R, re #36, I don't know why I thought of Pollock as an example of a challenge. Just convenient, I guess. At my intro to Pollock's drip paintings in the late '50s I was totally at sea. Those paintings seemed like pointless chaos. But exposure over time along with placing Pollock's paintings into my expanding context of formal visual language brought me to see Pollock's drip paintings as delicate, lyrical. So, Pollock's work challenged me in my illiteracy.

48.

December 11, 2009, 10:31 PM

Tim,

Pollock isn't a fair response, because of time, your experience then and now, rather than Pollock's or Bethea's paintings.

Since you brought up Pollock: A lot of abstraction of this type (color field painting, new decay) utilizes an association with visual phenomena, paint is coaxed into a (pleasing) chromatic textural surface marginally organized into a whole. It is similar in association to the photos of decayed painted walls (see Sean Kelly) It is this associated reference to the wall, the picture plane, which makes these paintings acceptable but not particularly challenging. I think what makes Richter successful at this is that his paintings don't pretend to be anything else, they don't have aesthetic pretense, they don't try to be good. It's mostly accident, so when they work they're somewhat miraculous in the sense of "how could all this shit look so good?" When they don't, they're just phenomena.

Pollocks drip paintings don't rely on this type of phenomena, in the world of "painterly phenomena," there isn't any reference for them. They do rely on Pollocks skills as a draftsman. The dripped lines eloquently describe a pictorial space linearly, a space which the viewer can find a way to engage in. It is capable of eliciting both deep illusion and the sense of kinesthetic movement.

Of the two Bethea paintings, Moss Man is the least successful for me. It is the most conventional and the pictorial space flattens out making the painting an exercise is painterly phenomena.

The other painting, which Jack linked I'm jokingly calling Eggo, is something else. Allowing for the limitations of only seeing a reproduction, Eggo does something completely different. Regardless of the acrylic techniques involved, as a viewer I am not engaging with the painting on this level as painterly phenomena. Rather Bethea has created a fairly complex pictorial space where all of the individual painterly elements serve to logically reinforce the paintings illusionary opticality in a way not unlike some of Pollock's paintings.

Most paintings of this type of abstraction die at the picture plane, the paint slides around on the surface and the pictorial space is as shallow as a cubist box. They lack the ability to generate a pictorial world of substance and mystery which is the very essence of painting itself.

I wouldn't have bothered to comment If I hadn't seen the second reproduction. I think Bethea is really onto something interesting here which could be easily derailed by backsliding into the world of known rules and prejudices of Modernist painting. I hope that doesn't happen.

49.

December 11, 2009, 11:00 PM

"I think what makes Richter successful at this is that his paintings don't pretend to be anything else, they don't have aesthetic pretense, they don't try to be good."

George, do you every read what you write and say to yourself "now wait a minute, this doesn't really make much sense"?

Just asking.

50.

December 11, 2009, 11:30 PM

George, if Richter does anything, he self-consciously pretends. His work is utterly premeditated. No accident there. Did he not edit his 'squeegee' output, for instance, because he saw some trick or other in some of them which he thought might catch the eye of a collector who couldn't distinguish a trick from etc.? Whew, that really seems cynical when I read it. But Richter seems to have gotten himself into a place where he's about the business of harvesting his bag of stunts, fun enough, but does it have any staying power?

As for Bethea's "Eggo," it presents a world of stuff put in illusionary terms. And? Not at all sure about 'substance and mystery'. Caveat: I've only seen Jack's link.

51.

December 11, 2009, 11:33 PM

Tim, you just recapitulated what I wrote about Richter nine years ago.

52.

December 12, 2009, 12:38 AM

Regarding Richter - Funny how everyone locked onto my minor remarks about him. I'm not very interested in his abstract paintings and have no interest in defending them. Whatever technique he uses, it looks like he's good at it. He just does it, they really don't feel like he is fussing with them.

I would add that when the beautiful young ingenue asks Richter if he works in "oils or acrylics" he has the right answer.

Tim, as far as Bethea's painting goes, you're entitled to your own opinion but consider that your are missing what the real issues in this type of painting are.

In my view the painting Jack linked is a breakaway work which is unlike the other paintings linked in this thread. As I said in my earlier comment, the problem for this type of abstraction, including Richter, is flatness -- they lack an optical pictorial space of any significant perceptual depth.

Some of this might be an artifact of working with canvas flat on the floor, how anyone can see what they are doing I'll never know. Whatever, it's a method that has been beaten senseless. There are a number of open issues which Bethea needs to explore. In particular, the relationship between all the 'objects' in the painting, their relative sizes in particular. Their shapes and coloration are irrelevant, essentially they could be anything, a point which opens up his pictorial possibilities considerably compared with his peers.

The danger lies in locking up the pictorial space of the painting in the surface, burying it in the scrapes and fissures of globby acrylic -- it's not necessary. Any decent painter should be able to make an image appear without all that fussing around. I also think there is a danger of getting too cute, of trying to hard. Again, I would suggest looking at Kandinsky, in this the late Kandinsky's. Although these are fairly geometric, several are masterpieces of composition, scaling, and dynamic movement which would be applicable even in a more organic pictorial world.

53.

December 12, 2009, 7:20 AM

Regarding Richter - Funny how everyone locked onto my minor remarks about him.

Not really, George R. You brought him up on the Bunny thread as well. It was bound to get some attention eventually.

Your comments about George's painting look more like an airing of your irritations with modernism than thoughts particular to his work. He's always been good at relating small parts to big parts, and one of the reasons that the high textures work so well is because they provide a wealth of small parts to compose. That variation in scale contributes to the effect of space, but most of that is being accomplished by value, specifically by putting lighter foreground shapes on a darker background, and lately by knocking areas back by spraying them with dark paint. They markedly defy flatness, both with composition and texture. That's neither here nor there in itself, but in George's case it works extremely well.

If working on the floor has been beaten senseless, then working upright has been beaten senseless ten times over. Obviously if you're going to work with this quantity of material it's going to have lie on the floor for a while. George used to keep a ladder in his studio so he could examine the horizontal work. In fact, back in grad school, he used to hang paintings off the side of the building from the second story, stapling the top edge of the canvas into the wooden railing, and then walk out into the green space and look them over. Back then he was working ten feet by twenty feet. Those were some extraordinary paintings.

54.

December 12, 2009, 8:38 AM

Another aside into Bannardville: I'd left the JPEG of Bannard's Courier up on the laptop and wife caught sight of it.

She's completely in love with it. She wanted to know if she could buy it. I explained that Bannard is, unfortunately for our budget, a "real" artist and his work goes for many thousands of dollars. (Not that two thousand, or, heck, even five hundred isn't well out of our price range.)

Nevertheless she's totally in love. I showed her Gideon, which is the one I like, but she prefers Courier.

55.

December 12, 2009, 8:51 AM

"If working on the floor has been beaten senseless, then working upright has been beaten senseless ten times over."

Yes, of course, and he comes perilously close to equating good painting to factors of depth illusion, which he seems to not be able to see in George's paintings.

I think MOSS MAN is deceptively bland and "naturalistic". When I first saw it my eye judged it better than my head did, becasue hy head said "simple pattern of rough pale green on plain darker background", which was accurate but dismissive, but my eye caught the curdled "boiling" effect of the green, which said "color coming at you".

These paintings fiddle with deliberately dopey composition to get color & surface effects across, something I can sense a lot better than I can say.

56.

December 12, 2009, 9:56 AM

Just now my wife asked me why I hadn't gotten her a print of that Bannard painting yet.

"He doesn't do prints," I said.

She made a sad face.

57.

December 12, 2009, 10:10 AM

Incidentally -- I keep coming back to the laptop in between bouts of cleaning the living room preparatory to putting up the Christmas tree -- Jack only linked to the low-res image of that paintings, but I highly recommend going to the full Flickr stream and also reading the comments. The thread under Gideon shows people working and thinking in abstract art at a very high level. The idea of George and Darby going back and forth on cropping, while names like Leger, Matisse, and Mondrian come up -- it's the kind of environment I dream about.

Maybe I should move to Miami. If I'm going to be an unfulfilled artist, I might as well do it near interesting people.

58.

December 12, 2009, 10:13 AM

Chris, tell her the painting would probably be too big anyway (it's 54.5 x 52.5 inches), unless you have that kind of wall space, and even then it would probably take over your house. I don't remember the actual price (low five figures), but compared to the price of a smaller, run-of-the-mill and inferior Richter, it's a bargain.

59.

December 12, 2009, 10:30 AM

If we could find room for a 50-inch TV, we could find room for a big painting. I'd just take down one of my own.

The low five figure price would be fine as long as there's a decimal point about halfway through. Somehow I suspect not.

Right now I'm using the 50-inch TV to show the painting. That makes it about half its actual size. (The TV isn't 50 inches tall, just diagonally, of course.)

Maybe we could sell one of the kids...oh, who am I kidding? We'd have trouble giving them away with hundred-dollar bills pinned to their shirts.

60.

December 12, 2009, 10:42 AM

the recent bannard show which had courier also had some of the early brush and cuts which these new paintings came from.

on www.bannard.com see lithia 1993, it is one of the best of the earlier pics if no THE best and interesting it is the one closest to these new ones in that possible figurative connections can be deduced. other old brush and cut day glow pics have a more similar color palette, but the composition on lithia shows a nice connection to the current work in another way. and it is an amazing pic if you have not seen it.

61.

December 12, 2009, 10:45 AM

Well I've done all the reading and followed all the links. Thanks Franklin for posting the two relatively good quality images of G. Bethea's paintings. I'd love to see better images of his early large paintings. They're not very clear on his website. I appreciate DCP's bringing up the issue of the ethical life and how it relates to the art process and abstraction. John clarifies the issue in #5 and of course Greenberg even more so in "Autonomies of Art." (and I love Terry Fenton's Sascatchchewan landscapes - what incredible skies and space). Looking at Celaya's paintings (as much as I can judge from a few reproductions), I don't see any link at all between his sentiments and his actual work, making the case for me for the autonomy of art. My teacher and mentor Kaji Aso used to say "Art is not life. Art is an illustration of life," and was an example for me of how to live an ethical and engaged life as an artist without resorting to simplistic statement and commentary - without saying anything in particular in fact, while still living a life richly engaged in metaphor. Piri's book is on my Christmas list and hopefully, if I've been good enough, I'll be reading it Christmas day.

Finally, I'll share this: I took my son to the MFA yesterday for a quick visit after making a furniture delivery in Boston. He's just decided to change his major to art at the community college here after much thrashing around and after throwing himself into a drawing class this past semester as a refuge from statistics, sociology and french. We saw (in order of our ramble): Toulouse-Lautrec in a small hallway show ("how do you pronounce his name?"),with the odd Bonnard thrown in; Sargeant (portraits, Venetian studies), Whistler Nocturnes, in a room of contemporaries including a fabulous Herter Brothers sideboard and japonesque chairs, 1890 or so, that relate to what I've been doing with my own furniture designs; then a mixed room that included Pollock, Max Beckman, a Morandi, some contemporaneous Italians who I didn't know: And then some contemporary galleries that included art related to music including John Cage scores; then the large glass piece (installation really, though it's more like a mirrored room turned inside out), by Josiah McElheny, which we agreed was fantastic; and we ended in The Secrets of Tomb 10A, Egypt 2000 BC. Almost all this, except the Egyptian art and a few things he knew from reproductions, was new to the kid. Yikes. Make that 30,001 art school grads in 2012.

62.

December 12, 2009, 12:06 PM

F. Ho Ho Ho. I brought up Richter because I thought it was totally ironic that the world renowned king of the squeege painters would raise the ire of all the other squeege painters here. (except John and Piri who couched her dismissal with a I'll have to go back)

And now, I see you have a little more to say about Bethea's paintings. If you fancy yourself as an art writer, then maybe that's what you should have done in the first place. If you consider the makeup of the art audience, those who will be reading something you write, you are going to find that there are some people who buy the current program, their minds can't be changed. The remaining audience is composed of KH bashers to one degree or another, those who more or less see things the same way you do.

You should consider the most effective way to use the alloted word-space you have alloted to you in order to help make the artist's (Bethea) paintings accessible and understandable. It is not a crime to attempt to give the audience a hint about what to look for in a painting -- why else is someone like Richter stealing the show. All this blather about "taste" is elitist bullshit if you as an art-writer aren't willing to provide some guidance towards connoisseurship.

Now specifically what Franklin alluded about what I wrote. I have no irritations about Modernism, it was exciting and inspirational to me as a painter. I happen to think it's over with but don't feel it's worth arguing the point.

I have no problem with "texture" in a painting. I do think that paintings which rely on paint phenomena, including texture, fall into a class if image making which exploits the "corroded wall" look. This is a very popular strategy because is provides certain visual clues to the viewer allowing them to accept the surface as decoration. Unfortunately almost all these paintings look very similar to one another which is why very few achieve high prices in the aftermarket.

Franklin said They markedly defy flatness, both with composition and texture. That's neither here nor there in itself,...

To the contrary, this was my whole point (I hope GB is listening). The major problem in abstract painting today is the "working space." The residual problem has been the notion of "flatness" as some sort of requirement. Now any painter with a few paintings under their belt knows that a painting is nothing more than a marked surface. There is no literal space behind the picture plane but their can be the illusion of space which occurs because of how our visual perception works. The creation of illusionistic space within a painting requires an acknowledgment of the surface but that's all. (example, Olitski's edge marks)

The process of creating a working space, illusionary or not, is linked to the idea that a painting presents a world space as envisioned by the artist (the artist's world) What a painting attempts to do is to allow the viewer to suspend their disbelief and enter the world of the painter. Simple enough, but taking this farther than a textured, scraped, and colored surface is not a trivial pursuit but unfortunately where most painters stop.

One of the phenomena which has occurred over the last decade is the widespread use of digital reproductions of paintings. I think this is affecting how we see paintings, in essence a digital image is equivalent to the "view in the mirror" trick painters have used for decades. With this idea in mind, I addressed the second painting of Bethea's and suggested it was a breakaway work.

Since I am only looking at the jpeg, I am just seeing the image of the painting, not it's physicality. Moreover, I am suggesting that it is the image that is important, the delightful ordering of the pictorial space, and not how he arrived at it. What may be occurring only by accident here because of a painterly interaction with random bumps on the surface, is a visual clue to a whole other path forward for his paintings, a path which diverges from what others have been doing in this particular niche of painting.

Mechanically, I don't think it's necessary to rely on either texture or process to move this program forward, but then I don't have to make the paintings and Bethea will have to start somewhere.

I still think it's better to work on the wall, but then I spend more time looking than actually painting.

63.

December 12, 2009, 1:25 PM

First, to Franklin(#27). You may find abstraction "limiting," but many other painters have found it liberating -- the opportunity to work with shapes & colors alone, without being tied down to the necessity to represent something. Helen Frankenthaler expressed this outlook beautifully, when I first interviewed her (for Time magazine, upon the occasion of her 1969 retrospective at the Whitney). In the early 50s, when she and Greenberg were going around together, the two of them used to go out into the countryside to paint landscapes; then she'd return to her studio to paint abstracts. "The landscapes were the discipline," she told me. "The abstracts were the freedom and the joy." Obviously, though, preferring to paint either abstract or representational is a personal choice, and good work can be done in either category.

Second, to George R.(#52 & #62) You seem to be tied down to the standard misinterpretation of Greenberg's position on "flatness," as he discussed it in "Modernist Painting" (1960). I discussed all of this in the June issue of my online column, upon the occasion of a two-day symposium at Harvard devoted to Greenberg. In addition to mentioning Greenberg's 1978 postscript to that essay, in which he dismissed the notion that he advocated "flatness" as "preposterous," I also advanced a theory regarding "Modernist Painting" itself. In brief, I suggested that in this particular essay Greenberg was merely describing the development of abstract painting up to and through the 50s, and including in his description not only the abstract painting he admired (from Pollock up through Noland, at that point) but all the abstract painting he didn't admire (most of the second-generation abstract expressionists, who were working out of de Kooning, and slathering on the paint without rhyme or reason). He wasn't recommending that anybody imitate the bad abstraction, any more than he was saying one should imitate the good -- both were equally "flat." And where is it written that "flatness" is a "problem"? Greenberg again: "art cannot be prescribed to."

You, George, may think modernism is "over." Maybe it is for you -- that's your problem (though God knows it's shared by a heavy majority of those people who fancy themselves as art lovers). I don't agree, though, not while we still have good work being done -- and it is being done, even though it doesn't get shown in Manhattan very often, and almost never gets the publicity it deserves. I try to review good modernist exhibitions in my column whenever I can see them (and by artists who are younger than the stars of the 60s, as well as the 60s stars themselves), but such work is created these days over a very wide area, and exhibited as often as not outside of NYC.

If you're curious as to my final opinion of Richter, that review is contained in my December issue, which went on view this past Sunday (12/6). In brief, I concluded that Richter has a little something (not much) and that 3 out of the 47 works in the checklist were at least "good" -- not very good, & certainly not great, but better than the rest ---hardly enough to enable him to deserve the superlatives being heaped on him by the sort of critic who goes along with majority opinion instead of stopping to question it.

Third, to David (#61) I do hope you get my book for Christmas, and I do hope you enjoy it.

64.

December 12, 2009, 2:06 PM

Piri, Permit me to quote a few quotes from

http://quote.robertgenn.com/auth_search.php?authid=5553

"Limitation of means is a precondition of excellence. Creative freedom chooses its limitations. Destructive freedom rejects them heedlessly."

"Too much freedom inhibits choice. Constructive narrowness clarifies choice."

"Convention and restriction release inhibition and provoke the imagination."

In other words, in art (and in most human activity) limitation and liberation are not opposed, they are the same thing. This is what Franklin mean by "fruitful limitation".

65.

December 12, 2009, 2:19 PM

George R sez:

What a painting attempts to do is to allow the viewer to suspend their disbelief and enter the world of the painter.

This is possibly what some painters are aiming for, but it's hardly the only way to paint.

Is this the same George as the one who was slumming earlier, and who used to comment here, or is this a whole new George?

66.

December 12, 2009, 2:37 PM

The best cubist pictures of 1910- 11 were very restrictive - pared down brown,black,and white paint, occasional hits of blue when Picasso was on the coast. They were robably there best pictures and some of the best of the last 100 years.

67.

December 12, 2009, 2:40 PM

My opinion that Modernism is over is related more to changing history than anything else. The evolution from an agrarian society to an industrial society provided the major impetus towards the idea of the "Modern" I believe that this social change to the industrial society has been replaced by the transition to an information based consumer society, we are "Modern." The major impetus here is the internet which is changing art as we speak.

Regarding Richter, I looked at the jpegs on the gallery website and decided it wasn't worth seeing the exhibition. I just really don't care. I did see an exhibition of 1950's Paris abstractions by Sam Francis (at L&M Art) which I liked. Tomorrow I'll spend an afternoon at the Guggenheim seeing the Kandinsky's -- best exhibition in years.

Correct or not, Greenberg is stuck with "flatness" - it just won't go away.

Disregarding flatness. The problem (failure) of so much of the thick paint abstraction (except recent Poons) is that is is nothing more than paint phenomena which relies on the corroded wall association as a method of engaging the audience. Another set of this type of painting is utilizing the physical phenomena to act as a form of drawing within the painting. I suppose in itself this wouldn't be so bad but the danger lurks that the painter becomes too enamored with the tricks of the process which then also becomes problematic. In this respect I see little difference between Richter and Bannard for example. I think Bethea escaped it marginally and that Larry Poons' last exhibition was one of his best.

The question that occurs to me is what is all this process based drawing in these paintings all about? Why don't the artists just get on with is and make a painting which doesn't have to use all the lumpy gooey paint as a crutch? A rhetorical question might be are these painters using process accident to do something they have a conceptual or historical bias against?

Further, I wonder if anyone is thinking about how we actually see a painting, how we process and interpret what is there. What actually is happening when the viewer is looking at a painting? Remembering that the painter spent days looking but the viewer spends about 30 seconds, maybe less, before moving on. (Really, I timed people at this at a couple of venues) What happens in that 30 seconds? A painting is an accumulation of thousands of small decisions expressed visually. Whether or not the viewer is consciously aware of these decisions is irrelevant, their final response will take them into account subconsciously or consciously. Further the viewer will make subconscious associations during the viewing process in an attempt to understand (decode, interpret) what they are seeing. Abstraction is just a different way of ordering this visual information.

68.

December 12, 2009, 2:44 PM

Chris, it's the same George you all love to hate. I was trying to avoid confusion with George Bethea

Re: What a painting attempts to do is to allow the viewer to suspend their disbelief and enter the world of the painter.

If this doesn't occur, the paintings fail.

69.

December 12, 2009, 2:57 PM

"Fruitful limitation." Wow! would I like to see this in action. As an exercise all the floor painters should stretch up a canvas and paint on it orientated vertically -- the same stuff as you always do without the pour and scrape -- then we'd see what you're really about. Yeah baby, simplify.

70.

December 12, 2009, 3:00 PM

"Fruitful limitation." was by me not B, sorry about that.

71.

December 12, 2009, 3:46 PM

I don't hate you, George. Not even in that "you're beneath notice" kind of way. I actually missed you.

What a painting attempts to do is to allow the viewer to suspend their disbelief and enter the world of the painter.

If this doesn't occur, the paintings fail.

I don't see what belief, or disbelief, has to do with a painting. Suspension of disbelief is a verbal, textual thing. You don't have to have any belief to view a painting, except perhaps in the painting's existence, which I must admit is rather hard to disbelieve.

You've got this idea, with this statement here and your earlier assertions about George B.'s depth of field, that viewers must be approaching paintings as windows into some space behind the frame -- some world they can enter. That very idea was one of the foundations of painting questioned by Modernism. Playing with how deep the pictorial space seems to be is what Cubism is about.

I think it's much more fruitful to approach painting as making shapes which trigger certain neurological responses in the viewer. Some of those responses are purely visual, and some subset of those responses engage neural structures associated with depth perception. But they don't have to. Some responses are emotional, some are physical, some are deeper and some are shallower. There's no necessity for there to be a space behind the frame -- I don't get that at all from, for example, Still or Newman.

72.

December 12, 2009, 3:51 PM

Piri, Opie speaks for me in this case. What one could do with abstraction is limitless. Abstraction itself is a limited problem. I don't mean that in a pejorative way in the slightest - you're limiting yourself in the studio as soon as you decide to do one thing instead of another thing. That abstraction has produced so much good work speaks well of it as a finite problem set.

George, Richter's use of a squeegee would matter more if the results were better. As I said above, some of his larger squeegeed oils were quite good. These smaller, more recent ones, not so much.

I wonder if anyone is thinking about how we actually see a painting, how we process and interpret what is there.

I've thought harder than anyone I know about what happens when someone looks at art. Doing so gave rise to my distinction between lookers and readers, as well as my theory of the panjective from a couple of years ago.

I think that now that I've been hired by several publications, one of which is The New Criterion, my status as an art writer has been externally formed apart from whatever I fancy myself. As it happens, I already have written about George's work at some length. Much of the rest of your comments are attempting to solve problems for either me or George that I don't believe that we're having in the first place. Thank you for thinking of us, though.

73.

December 12, 2009, 4:13 PM

One of these days you're going to have to tell us how you got hired by several publications. I suspect the answer is something like, "I applied," but I'm curious anyway.

74.

December 12, 2009, 4:36 PM

Chris, "Willing suspension of disbelief" is a phrase frequently used in regards to film. All I mean is that the viewer "gets into" whatever world the painting presents, from Ryman to Velasquez, it doesn't matter, good paintings have a consistent logical presence that the viewer is willing to accept.

Pictorial space can take many forms, I'm not advocating one necessarily over the other, nor am I suggesting that that the painting needs be like a window. Forget about what you think Modernism was questioning, that's all past. Any spatial organization is just as valid as any other. It is illogical to say one illusion is better than another.

Anytime you place any shape/object on a canvas you alter the viewers spatial clues. The viewer either sees a shape on a flat surface, or a shape in a perceived space, or both simultaneously. The working space is the way these shapes are organized on the canvas, if two shapes overlap, one is in front of the other, etc. A 'good' working space has its own logic which must be consistent across the painting or the painting will fail.

"Logic" as used above can have many interpretations. Analytical Cubist paintings (Picasso, Braque 1910-12) have a precisely developed space which can appear transparent and deeper than just the drawing would suggest at first glance. Other spatial logics can rely on what we know of the real world, or its reproduction or abstraction. There is no particular limit to the kinds of logics which may be developed, but what's important is that they are consistent.

In the case of Bethea's paintings I think that his development of a pictorial space which is not stuck on the surface is significant. What I mean by this is that while his paintings acknowledge the surface, the visual/perceptual activity does not feel like it is locked down, pasted on, or scraped off, of the painting surface. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this (Newman, Still) most of the current painters taking this approach seem stuck in the same way all the lesser AE painters were 'stuck' The paintings all look alike, sometimes one's better than another, but for the most part they are not very compelling. I feel Bethea is working his way away from this trap, but I'll admit I could be wrong.

75.

December 12, 2009, 4:52 PM

Re #72. Franklin, I still get the feeling you're fighting the last war (pomo) which wasn't quite what I meant with I wonder if anyone is thinking about how we actually see a painting, how we process and interpret what is there.

You may have written about Bethea's work before but that doesn't count here, where you headlined the blurb you just wrote. Whatever, now that you've thrown your hat in the wring with the other art writers -- good luck.

My remarks about Bethea's paintings are a lot more open and honest than anyone else is going to express. Yes, he might think I'm wrong, but that's between me and him, not you. I think there is a value to hearing a response which comes from outside ones 'safe territory' and I don't see how anything I said could be construed as anything but complimentary and encouraging.

76.

December 12, 2009, 4:57 PM

You may have written about Bethea's work before but that doesn't count here, where you headlined the blurb you just wrote.

Have you been laboring all this time under the misapprehension that I wrote the blurb in the original post? Oh my.

77.

December 12, 2009, 4:59 PM

Franklin, excuse me but yes. So I must apologize to you and transfer my criticism onto WDB. Whatever, it doesn't change my opinions.

78.

December 12, 2009, 5:05 PM

Funny thing too, I had just listened to this which describes what happened from a scientific point of view.

THE SIMPLIFIER A Conversation with John A. Bargh

79.

December 12, 2009, 5:05 PM

Opie, your ideas about limitation equalling liberation are certainly interesting but paradoxical, which is to say contradictory & therefore necessary to define (as you have). Otherwise they are open to misunderstanding.

As for Analytic Cubism, George Bethea, I would agree that these are very great paintings, but I don't see their palette as narrow. To call this exquisitely and richly varied palette of grays, browns, beiges, blacks, blues (and sometimes pinks and greens) "narrow" is a cliche based in the assumption that Picasso & Braque were withdrawing from external reality and had to eliminate impressionist color in order to concentrate on their forms. My position is just the reverse: I say that these paintings represent a new and radical way of depicting reality, the reality of the Montmartre environment in which Picasso & Braque were living & working. My logic is too involved to go into here, but I will say that in the matter of color, I got my ideas from Michel Seuphor, Mondrian's biographer, who wrote that these grays & browns are the palette of Parisian street facades. When I once quoted him on this subject to Jules Olitski, Olitski's response was on the order of, I didn't know Seuphor had that much sense.

George D (is it? I can't keep all these George's straight). If Greenberg is stuck with flatness, it is only because so many people refuse to accept what he wrote for reasons best known to themselves. But then it's difficult to argue with somebody who passes judgment on paintings -- even Richters -- without seeing them. I may not like looking at the art of people like Richter, but I figure I can't knock it without having seen it. (And in this I follow Greenberg, who looked at a lot of art he didn't like as well as a lot of art that he did.)

80.

December 12, 2009, 5:10 PM

Sorry, it seems to be George R I was addressing on the subject of flatness, not George D.

81.

December 12, 2009, 5:20 PM

Piri,

Re: Greenberg and "flatness." I don't dispute what arguments have been presented here disputing this connection. I'll accept them as true. However in the real world, it's not the case, Greenberg and flatness are joined at the hip forever:-)

But then it's difficult to argue with somebody who passes judgment on paintings -- even Richters -- without seeing them.

Regarding Richter -- I've seen some of his squeegee paintings and I'm just not all that interested in spending the time to go see more. There are other exhibitions that are competing for my time and energy and I have to make choices.

As for Bethea's paintings I made it explicitly clear that I was going out on a limb because I had only seen the reproductions. For the most part I only addressed points which could be inferred from the jpegs.

82.

December 12, 2009, 5:23 PM

as a whole painting has certainly declined.

however good mr. bethea's work is I just

don't see it reaching the level of some of the

best work in the past.

83.

December 12, 2009, 5:26 PM

Re #79 The same point applies to the earlier paintings made by Picasso and Braque in Horta. If you see photos of the town, well it looks just like the paintings.

84.

December 12, 2009, 5:39 PM

George R sez:

Chris, "Willing suspension of disbelief" is a phrase frequently used in regards to film.

Thanks to the fact that I am not a complete nitwit, I knew this. Note that film -- at least in regards to suspension of disbelief -- is a verbal, textual medium. The suspension of disbelief is also used in fiction writing, which is obviously textual. The idea is that one can accept unrealistic plot twists through the willing suspension of disbelief -- in other words, "I will accept this as true even though it's clearly something that would never happen in the real world."

This only applies to paintings, as far as I can tell, with the greatest exercise of imagination I can muster. Unless we're talking about someone like Dalí, in which case you might need it to accept drippy clocks and so forth.

All I mean is that the viewer "gets into" whatever world the painting presents, from Ryman to Velasquez, it doesn't matter, good paintings have a consistent logical presence that the viewer is willing to accept.

I disagree most strongly. The only way I can go along with this is in the most metaphorical, least literal terms I can conjure up. Otherwise we're in that scene from Mary Poppins jumping into Bert's chalk drawings and walking around.

85.

December 12, 2009, 5:42 PM

Chris, you don't know much about painting, sorry.

86.

December 12, 2009, 5:55 PM

You're probably right, George, but probably for the wrong reasons.

87.

December 12, 2009, 6:19 PM

Piri_ yes, I agree the palette of the 1910 - 11 cubist pictures is not narrow. Both Picasso and Braque new the pictures would not work with amplified color. They focused on subtle value and color differences with earth tones. The best of these pictures for me are very simple in composition with thinly applied paint. Some of the pictures I'm talking about were harbor scenes. I can't remember the name of the town in which they were painted.

88.

December 12, 2009, 6:30 PM

Chris, it was under "Courier" that the discussion takes place, and there are other similar but less extensive comments under other paintings.

There's nothing better than having sharp eyes poke around the paintings and come up with observations & ideas.

(I write this earlier and didn't send it until now)

George B please use "Bethea". George R's comments are bewildering enough without mixing them up with yours.

89.

December 12, 2009, 6:33 PM

Bethea you may be thinking of the paintings done by Picasso in the summer of 1910 in Cadaques, on the coast of Spain. To me that was the apogee of Cubism and one of the high points of all painting art.

90.

December 12, 2009, 6:33 PM

George R, re your idea about believing/disbelieving: I don't know what would be in a painting to believe/disbelieve except an illusion of some kind, like space, and that is either sensed or not sensed, not believed/disbelieved. It's not whether I believe it. It's whether I get it. Also, I don't know where in the experience a viewer's 'willingness to accept' comes into play.

And, maybe you're calling 'logical presence' what I'd call 'integrity.'

91.

December 12, 2009, 6:39 PM

Piri of course the color is limited, deliberately very limited, to very unsaturated colors. Cubism would not have worked any other way. That it was subtle and beautiful and very varied is another matter. You seem to have some notion that "limited" = "bad"

That limitations are fruitful and lead to plenty in art, and much else in human life,is contradictory only terminologically. Think about it.

92.

December 12, 2009, 6:45 PM

Opie- yes, Cadaques, and it was Picasso who did the specific paintings I referred to.

93.

December 12, 2009, 8:05 PM

Yeah, Opie, well I never studied abstract painting with Darby Bannard at Miami U., so I have my own understanding of limited. I can sort of see what you're getting at, and I'm sure it's very helpful for a student to think in terms of limitation & discipline, even or perhaps especially if s/he wants to make good abstractions, as opposed to just slathering the paint around, but one of my dictionary's definitions of "limited" is "lacking breadth & originality" so it has that connotation for me.

Would you also say that the impressionist palette is limited because it doesn't have grays or blacks?

With regard to cubist paintings made outside of Paris, Seuphor specifically says that when Picasso and Braque went on holiday they brought their Parisian palettes (figuratively speaking) along with them.

I apologize to George R. for suggesting that he evaluated paintings without looking at them. But I resent not being considered part of "the real world" simply because I believe Greenberg meant what he said. Am I a figment of your imagination, George? How about all the rest of us here at this website? Are they all imaginary, too? I'm perfectly willing to concede that a majority of those people who think they know about art associate Greenberg with flatness, but then an unholy percentage of the US population still believes that God created the world in 7 days. Does that mean the people who accept the principle of evolution aren't members of "the real world," either?

As to "the information age," I consider this an overworked slogan designed for people who like to congratulate themselves on being up-to-date and in the forefront of Progress. The way I see it, history evolves much more gradually & not everywhere at the same time. To the extent that the term, information age, has any validity, it refers to those countries where blue-collar jobs have so largely been replaced by white-collar ones, but this has only become possible because those countries have displaced such a large proportion of their industrial bases outside their geographic boundaries--not because they've dispensed with industry altogether. This displacement is possible because nations like the U.S. can import such a large percentage of their assembly-line goods (everything from clothes to electronics to steel to automobile parts -- and these percentages can be staggering -- I give some of them in my book). In the countries that produce these goods, however, the industrial age is still very much in progress,and even an early stage of it, with the farm population migrating to the factories in the cities. I don't say they don't have the internet in China, but it's more like a thin veneer. (And even in this country, not everybody is online, not even everybody under 40!)

I do see a link between the loss of interest in modernism & the increased size of the white-collar class, though. That is because so many of the new white-collar workers are first-generation artlovers (or the children of first-generation white-collar art lovers from the 60s & 70s). Starting in the post World War II period, and the prosperity of that period, blue-collar workers were enabled to send their children to college, and these children subsequently used their college degrees to land white-collar jobs. Naturally, these children had to have white-collar hobbies to match, so a number of them took up art, but because they'd been raised in blue-collar homes, they hadn't been taken to museums as children. The result was that most of them had never developed any sympathy with or ability to appreciate modern art, especially abstraction (& it's not easy for most people to relate to abstract art, I say on the basis of 40 years of trying to interface between the art I love & the rest of the world). When pop came along in the 60s, the people who hadn't been adequately prepared to relate to abstract expressionism leapt with cries of joy on the pop art bandwagon, and that bandwagon has been rolling merrily along ever since (with its concommitant commitment to crumby abstract painting). Maybe in another century or so, the bandwagon will have successfully flattened out any good painting still being done, but for now I say, with Yogi Berra, it ain't over till it's over.

94.

December 12, 2009, 8:09 PM

as a whole painting has certainly declined.

however good mr. bethea's work is I just

don't see it reaching the level of some of the

best work in the past.

95.

December 12, 2009, 8:55 PM

In the formalist tradition of art criticism, flatness is inseparable from aesthetic value, or what Clement Greenberg—formalism's leading voice—defined as "quality." This aspect of Greenberg's doctrine has been the most polemical in recent critical reevaluations of his work, but nonetheless his definition of painting's reduction to flatness is still the most complete. Greenberg applied the Kantian model of self-definition to support his view that each art must isolate and make explicit that which is unique to the nature of its medium. The "irreducible essence" of pictorial art, he wrote in his 1965 essay "Modernist Painting," is the coincidence of flattened color with its material support: "Flatness, the two-dimensionality, was the only condition painting shared with no other art, and so Modernist painting oriented itself to flatness as it did to nothing else"

96.

December 12, 2009, 8:58 PM

Picasso's paintings from 1910 are here. The summer starts with OPP.10:015 and runs through OPP.10:078.

97.

December 12, 2009, 9:00 PM

George, I've read only one of Greenberg's books and maybe a handful of his essays and even I know a statement like "flatness is inseparable from aesthetic value, or what Clement Greenberg—formalism's leading voice—defined as 'quality'" is complete and utter bullshit, only believable if you've never read a word the man wrote.

98.

December 12, 2009, 9:01 PM

Also, I've read some Kant, and the phrase "Kantian model of self-definition" sounds like nothing I've ever heard.

99.

December 12, 2009, 9:12 PM

Re 95: I joined the Guggenheim Museum recently and with the membership I received a catalogue "The Guggenheim Museum Collection A to Z" There is a section for "Flatness" on page 110 which I quoted in part, in comment 95.

In the 70's Greenberg = flatness, in all the painterly dialogues, and it has stuck even into the present day as evidenced above. It's a shame because it really is a flawed concept. A lot of the time what matters most is what people think the truth is, we live in a world of illusions.

100.

December 12, 2009, 9:32 PM

Regarding the "Information Age" We are in it, no question. This does not mean that industrial manufacturing disappears but in the worlds largest economies, the USA and the EURO zone, information technologies generate more revenue by more than an order of magnitude than all industrial economies combined. The Industrial Age didn't penetrate all regions of the world at once but it didn't matter because where it became effective, in the USA and Europe, is where Modern Art was made. "Progress" is a term which belongs to the Industrial Age and Modernism, but not to the Information Age.

I believe the crossover between the Industrial Age and the Information Age was somewhere in the mid 1960's. Postmodernism was the runoff of the Modernist ideal distorted by the confusion caused by the rapid influx of information. The internet was 20 years old in March, but has really only been a factor in the culture for the last ten years.

In the next decade there will be a new generation of artists which have always had the internet, cell phones, texting, TV, iPods, Laptops, Photoshop, Facebook etc. Now, the human brain keeps developing until a person reaches the age of twenty. "Developing" means creating new neural pathways in an intense fashion. Because of this subtle fact, we have no way of predicting what young artists will be doing starting in about 10 years because their preconditioning is going to radically change whet we now call "taste"

101.

December 12, 2009, 9:40 PM

From a random search via google:

One poll (2004) by CBS has has 55% believing god created man and 27% believing in evolution.

Interestingly there was a poll that did a follow up some years later. This poll (1991) had 47% for creationism (God created man 10,000 years ago) and 40% for evolution.(man evolved God guided the process). However an addition 9% also believed in evolution (man evolved God wasn't involved) End numbers 47% to 49%

A follow up (1997) to the last poll, with the same numbers came out 44% creation 39% evolution with God and 10% pure evolution. End numbers 44% to 49%

However, among "scientists" the numbers to the same questions were 5% 40% 55% End numbers 5% to 95%.

A Harris poll (2005) found 64% agreed "human beings were created directly by God," 22% of adults believe "human beings evolved from earlier species,"10% that "human beings are so complex that they required a powerful force or intelligent being to help create them" End numbers 74% and 22%.

Enough with the numbers. "Surveys are also fairly consistent in their estimates of how many Americans believe in evolution or creationism. Approximately 40%-50% of the public accepts a biblical creationist account of the origins of life, while comparable numbers accept the idea that humans evolved over time. The wording of survey questions generally makes little systematic difference in this division of opinion."

What's to be done with human unwillingness to accept logical argument? Promulgate wrongheaded opinion or merely shake one's head over such mass delusions?

102.

December 12, 2009, 9:53 PM

My last was in response to the Guggenheim's catalogue essay on flatness.

This is in response to the discussion of the next generation. If we don't know what the next generation of laptop-users will favor, there's no guarantee that it will favor postmodernist over modernist art.

As to when the human brain stops developing, it depends on which scientist you talk to. New research is always being done, and some I've seen recently suggests that the human can continue to develop right up until death. In addition, the Wall Street Journal ran a very interesting article some time ago on how older brains have more accumulated knowledge on special subjects, so they are better able to do things like play bridge or recognize old-fashioned things masquerading as new ones.

103.

December 12, 2009, 10:00 PM

When I say that Modernism is over, I don't think it's a bad thing. As the world economies industrialized starting in the mid 19th century, people move from the farms into the cities. This urbanization was soon accompanied by a number of labor saving devices which reached an apogee in about the late 1950's.

With each new technological advance, the urban population became more "modern," you could see the progress visibly as autos morphed from boxy motorized carriages into streamlined vehicles where the form reflected their potential for speed. These type of transitions, very visible transitions, gave rise to the idea that society was progressing towards the future. "Progress" was the slogan og the Modern Era and this idea was picked up by art as well.

Progress became a slogan for the avant guard, for Modernist Painting, accompanied by the idea that it "must isolate and make explicit that which is unique to the nature of its medium." In the American postwar era this was an exciting idea which inspired some very great art. The quest for self definition inevitably came to an end, and with it so did Modernism. In the case of painting, I would suggest that late 20th century abstraction completed a formal definition of painting which had been ongoing for over a century.

Once you enter "stripe paintings" into the lexicon of painting, all stripe paintings refer back to the initiator losing their ability to remain avant guard. It doesn't mean that one cannot make stripe paintings, but that one has to find a way to use the paradigm of stripe paintings in a different way. Rather than defining the language, one has to exploit its existence -- this is going to be the mandate for painting in the information age. It's a brave new world.

104.

December 12, 2009, 10:13 PM

Piri, Your Google search makes my point about the information age -- but for a few researchers, 10 years ago your comment would have been impossible.

Postmodernism is dead. I suggested this here after the publication of Hal Fosters book eight years ago. On the street, this also seems to be the opinion. As I mentioned, in the NYC art schools, it's just a page in the book.

We are in the dead zone. The baby boom intrelligensia have already done their thing, Modernist or Postmodernist, and the critical community seems to be in a state of confusion FWIW, I have a few very very smart Facebook friends in their early twenties, they see Postmodernism as a gigantic failure which they reject. What they are grappling with is a humanist application of interdisciplinary thinking, art film, literature and psychology (I scare them with math or economics).

105.

December 12, 2009, 10:14 PM

As you say, George, your time is limited & so is mine. I have letters to write, which I have been putting off all day,so I shall refrain from attempting to deal with your last. I just wish that instead of proclaiming over & over that modernism is over, you'd get out and look at what there is to see (preferably without feeling in advance the need to prove that modernism is over).

106.

December 12, 2009, 10:14 PM

George, we have had at it so many times in the past over the same territory, and every time I argue with you is it an exercise in futility. because you make absurd statements at absurd lengths - like the Greenberg/flatness business - and then, when challenged, dodge and weave all over the place. It is like trying to pick up mercury, or catch the proverbial greased pig.

I'm going to cease and desist until I can't stand it any more.

107.

December 12, 2009, 10:38 PM

Piri, regarding brain development. What I was referring to is a condition similar to the one which facilitates the learning of languages. I read the same articles you did on continuing development which keeps me hopeful.