Next: A second tulip mania (120)

Rouault at Boston College

Post #1263 • December 4, 2008, 10:41 AM • 3 Comments

I have been going back and forth on Rouault for a long time. He wanted to make printmaking and painting function like a stained glass window, with heavy black outlines filled in with pure, luminous color. Van Gogh similarly tried to adapt cloisonné to oils, and perhaps nothing tooled by hand is as inherently beautiful as stained glass, so the choice would seem promising in more than one respect. In execution, those black outlines, sometimes as thick as tree branches, limned the full woes of expressionism in all its pathos and unsatisfying drawing. Except where it doesn't, and here I become unsure. Sometimes the drawn elements are surprisingly fluid and accurate, and the tone is bouyant.

Rouault ran on a fuel of sincerity and emotional fervor. He identified with the lowest rungs of society, wanderers, prostitutes, and saltimbanques, whom he depicts with consummate sympathy, while his rendering of Nietzsche's übermensch is a frame-filling, fat-necked homunculus, a blocky wall of warmongering idiocy. His pictures of Jesus show him mocked or crucified, excepting a protracted series of heads, recalling the Buddhist practice of painting Bodhidharma, showing resignation and bottomless peace brought about by crushing suffering. Among many other virtues of Mystic Masque: Semblance and Reality in Georges Rouault, a dozen or so of these Christ heads hang together on the two-story wall in the McMullen.

With sincerity of this caliber, one could argue that everything else is a technical problem. Indeed, I'm inclined to look past a lot of the shortcomings in the images' construction, as their awkwardness, for the most part, stopped grating on me after seeing a few rooms of it. Filling in a drawn outline is a dumb way to put a painting together - humanity invented oils to get around precisely that problem - except that it can work beautifully, which goes to show you how much judgments like that are worth in the end. For any number of flaws, they deliver an enormous cargo of feeling, as if the artist had loaded a horse-cart with paving stones and made it win a road race against an Aston Martin. I think of the rougher bits as notes left for Beckmann: "Max, see if you can do something with this - Fondly, G."

Point in fact, I found a ton of stuff to steal. Simple willingness to let the lines curve solves the problem of the figures looking like they've been built from fence posts, thereby enabling a huge vocabulary of imagery ranging from caricature to Fauvist elegance. Colors can look damn good next to black. Perhaps best of all, those of us whose artistic proclivities don't intersect with irony at all have Rouault as a beacon. It's hard to think of a contemporaneous artist, to say nothing of a contemporary one, whose work so resoundingly issues the dictum to love with all your heart.

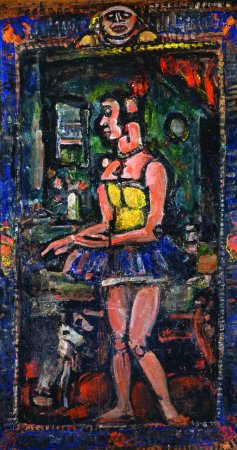

Georges Rouault: The Dancer (Danseuse), 1930-31, oil on paper on cloth, 85 x 46 inches, Fondation Georges Rouault, Paris, © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

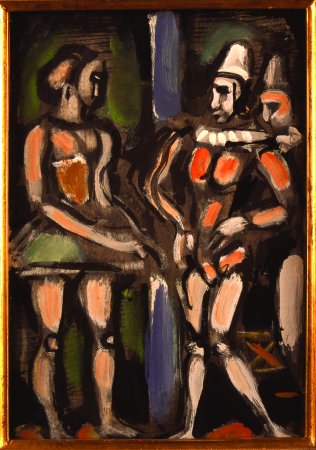

Georges Rouault: Parade, 1934, oil, ink and gouache on canvas, 11 4/5 x 7 7/10 inches, private collection, © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

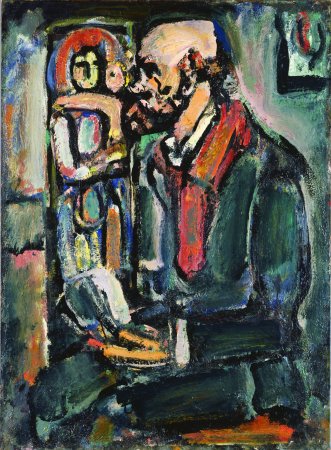

Georges Rouault: Are we not all slaves? (Ne sommes nous pas tous forçats?) 1920-1929, india ink, oil, and gouache on paper mounted on canvas, 40 1/10 x 28 3/4 inches, Fondation Georges Rouault, Paris, © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Georges Rouault: Pierrot with a Rose, 1936, oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 24 5/16 inches, The Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White Collection, photo: Graydon Wood, © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Georges Rouault: Verlaine with the Virgin (Verlaine à la Vierge), c. 1939, oil on paper mounted on canvas, 39 3/4 x 29 1/8 inches, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Georges Rouault: Whore, or Woman with red-brown hair (Fille, or Femme aux Cheveux Roux), 1908, watercolor, gouache, and pastel on paper mounted on board, 28 1/4 x 20 1/4 inches, courtesy of Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

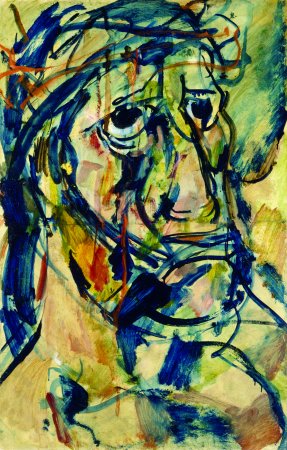

Georges Rouault: Head of Christ or Christ Mocked (Christ aux outrages), 1905, oil on paper mounted on canvas, 39 x 25 1/4 inches, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Georges Rouault: Singer with a White Plume (Chanteuse à la plume blanche), 1928, oil on board, 29 1/2 x 25 5/16 inches, Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Sydney M. Shoenberg Sr., © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Georges Rouault: The Wounded Clown (Le Clown blessé II), 1939, oil on paper on masonite, 72 x 47 inches, Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, Museum Purchase: Currier Funds, 1964.2, © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

2.

December 4, 2008, 8:54 PM

In certain cases, artists (not only visual ones) can compensate for significant deficits in talent or skill by special traits of character and/or force of will--in other words, by sheer conviction and commitment to communicate their art. At times, there can be a kind of heroic quality to this, as it is clear that the artist is up against significant limitations which remain evident, and the struggle to prevail demands complete engagement.

That does not mean or guarantee complete or unassailable victory, but it commands respect and admiration, and it makes an audience considerably more sympathetic and empathetic. True, one could say it's a triumph of emotion or psychology over cold, hard reality and not-so-pleasant truth, but the fact is it can still work.

This phenomenon is probably, understandably, more likely to occur in performing arts. Maria Callas is a classic example. She never had a great voice as such, and many say she wasn't even a true soprano but a pushed-up mezzo (but there aren't too many mezzo starring roles). Still, she was dead serious, totally committed and involved, and when she went onstage, she meant business and then some. It was no-holds-barred, take-no-prisoners, I'm-here-to-conquer time. She usually succeeded.

3.

December 11, 2008, 9:47 AM

Maybe this is the case with Francis Bacon, too...

1.

Chris

December 4, 2008, 7:34 PM

Thanks for this; well written, insightful, sympathetic. Did you know that Rouault was apprenticed at fourteen as a glass painter and restorer?

I had long regarded Rouault as a bit of a guilty pleasure, an artist others might think of as a lightweight and too French, you know, so I didn't mention him much, but it turns out that his name has come up recently with other painters who I respect and they nod their heads in appreciation, too.

Earlier this year in Paris, while walking from one place to another in the Latin Quarter, we came across Eglise de Saint Séverin. We didn't expect the mid-60's windows by French abstract painter Jean René Bazaine, which were surprisingly strong, beautiful, and moving. And the interior of the church has quite interesting architectural components- recommended.

I entered a small side chapel where a few people sat and prayed. Around the periphery was a set of framed (and rather cheaply framed, I thought) black and white lithographs of the Stations of the Cross by Rouault. The setting was quiet and austere. Because of those praying I chose not to walk around the chapel and look at each print closely; collectively, though, they added to the solemn but joyful feeling in the chapel on a cool but sunny early spring afternoon. I found a photo on Flickr, not mine, which provides a glimpse of this scene.